A tale of a simple pizza wish that falls down a math and optimization rabbit hole.

The Application

Don’t worry, we’ll get to the math soon enough, just have to give some background first.

All of this started in late August of 2018 after helping one of my friends move into his new house. My friends and I all help each other out whenever one of us has to move, usually with the promise of the person moving ordering pizza for everyone at the end. I’m unfortunately personally against some of the group’s more popular toppings of mushrooms, pineapple, and pepperoni. This usually means that I either have to have an active voice in the pizza ordering or risk picking stuff off of a pizza even when we get like 3 different pies. On this particular day, I was still moving stuff when the order was called in, meaning that I was greeted with 3 pies where my best option was to pick mushrooms off of one. It was at that point that I decided something needed to be done.

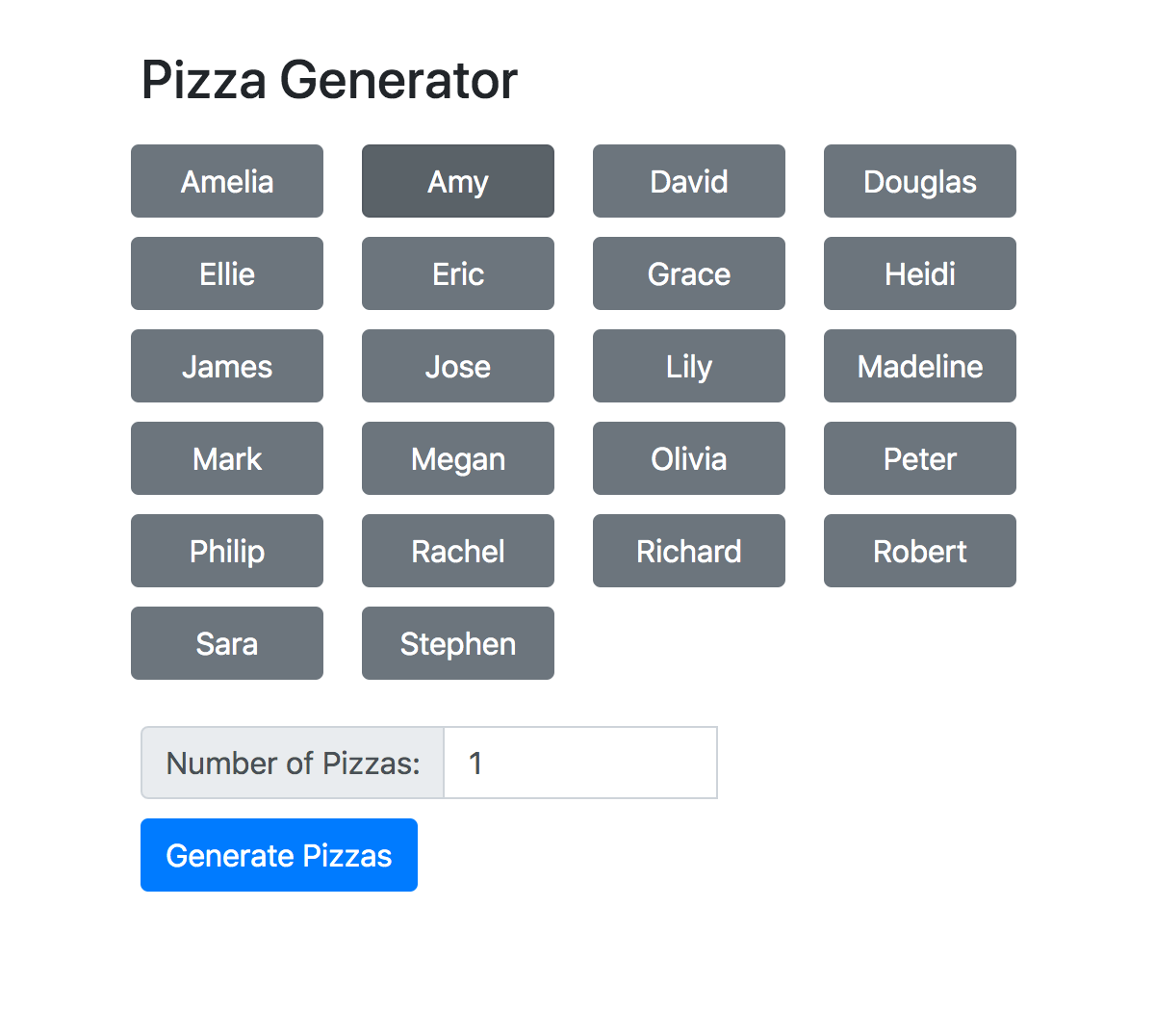

That afternoon I went home and immediately started writing the “Pizza Solver”. The goal was simple: Take in everyone’s preferences and the number of pizzas desired and output the ideal groupings of people to maximize topping overlap. After a bit of infrastructure work to get it hosted on my personal server and register it under a cute domain ending in .pizza it was up and working! You can play with a public version here. (The names have been replaced for my friends’ sake.)

|

|

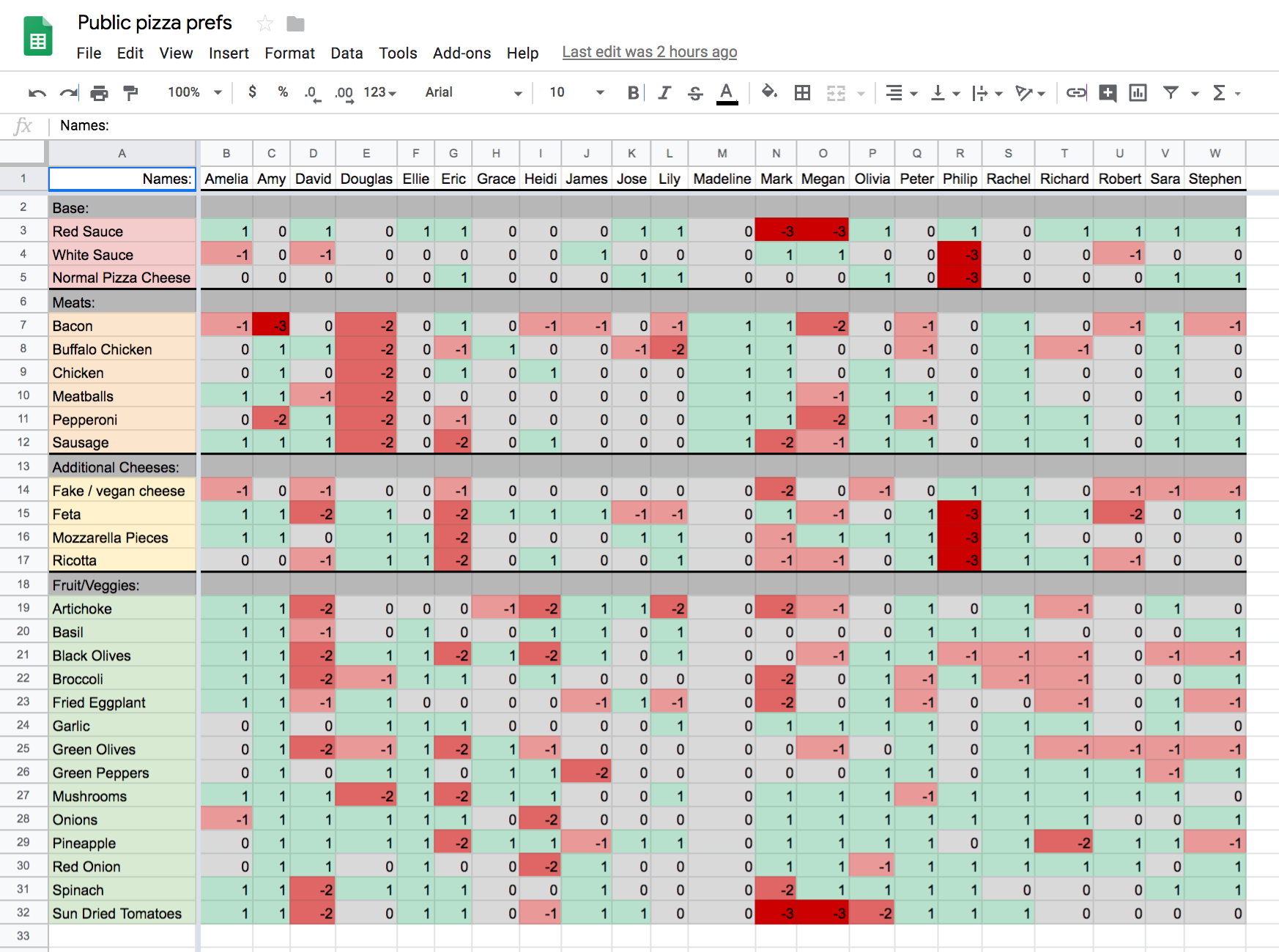

The interface was as simple as the concept. Users would first go to a shared Google sheet, fill out what they liked (1), didn’t care about (0), disliked (-1), hated (-2), and were allergic to (-3). Users would then go to the homepage, select by clicking all of the people at the event, the number of pizzas desired and after hitting “Generate Pizzas” would get a page like this:

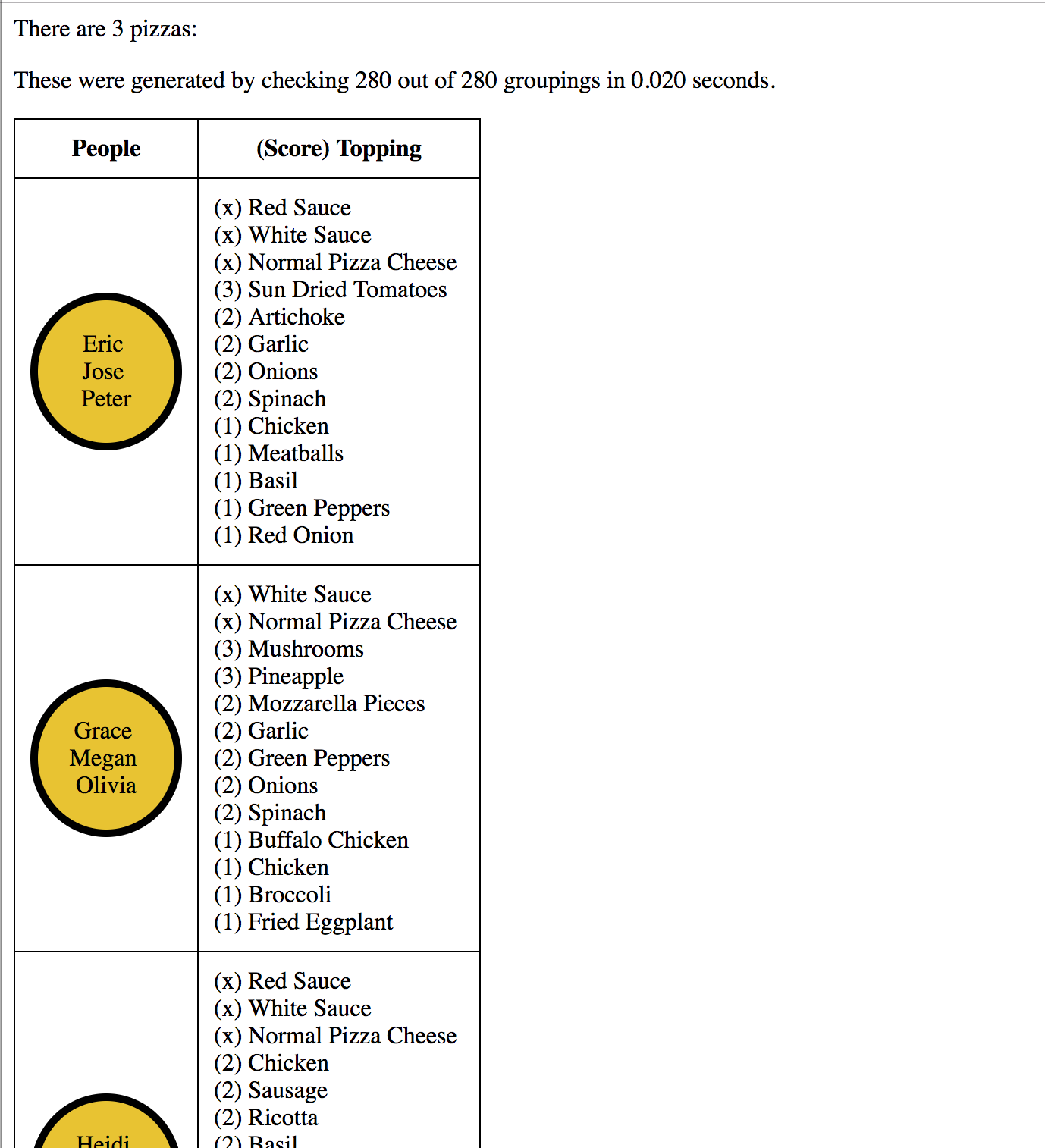

|

Here you can see that it groups people into pizzas, and shows all the toppings that everyone likes along with a score for each topping showing exactly how “liked” it is. It doesn’t dictate the pizza each group has to order, but instead just shows all toppings of shared interest and the people can decide for themselves what subset of them to get. In this example image, Eric, Jose, and Peter would all be very happy getting a Pizza with onions, sun dried tomatoes, and spinach.

Within a few short days I already had a few improvements over the original:

- Reduced clutter by not showing toppings everyone is neutral about

- Changed which set of groups was the “best” by maximizing the minimum of the group scores rather than the sum of the scores. (Because one group with a great pizza shouldn’t offset another group having a bad pizza)

Those improvements stood unchallenged for almost a year. The website even came in use a few times during that year as small events needed pizza. But there was a monster of an implementation detail lurking under the surface waiting till the next time we helped someone move to rear its head.

The Math

Lets take a step back and look at some of the math behind the impending issue. In order to present the best possible grouping, we must first find and score all possible groupings. Putting scoring aside for a moment, first we have to generate every possible group. There are a number of ways to go about this, and I’ll present the ones I iterated through in the order I thought of them.

The Problem Statement

Generate all possible groupings of n people into k groups where the groups are as evenly sized as possible. (We don’t care about wildly uneven groups because when ordering pizza you don’t split into groups like 6 people, 1 person and 1 person)

Solution #1

The simplest way to ensure you have all possible groups is to just take every possible permutation of the n people and then split each permutation into groups after the fact. For example, 6 people into 3 groups would first become

A,B,C,D,E,F

B,A,C,D,E,F

C,A,B,D,E,F

A,C,B,D,E,F

B,C,A,D,E,F

C,B,A,D,E,F

C,B,D,A,E,F

...

and then become

(A,B) (C,D) (E,F)

(B,A) (C,D) (E,F)

(C,A) (B,D) (E,F)

(A,C) (B,D) (E,F)

(B,C) (A,D) (E,F)

(C,B) (A,D) (E,F)

(C,B) (D,A) (E,F)

...

This solution technically works, but as you can even see from this relatively small example that it generates a bunch of useless duplicate groups. For our purposes we don’t need both

(A,B) (C,D) (E,F) and (B,A) (C,D) (E,F). (Lines 1 and 2 above)

Just one of them will suffice, which brings us to our second solution.

Solution #2

Because we don’t care about ordering, we should instead be looking at combinations instead of permutations. A different way to look at the problem is to instead select people group by group. To do this for 6 people into 3 groups we’d first get every way to choose 2 of the 6 people.

(A,B)

(A,C)

(A,D)

(A,E)

(A,F)

(B,C)

(B,D)

...

That becomes our set of first groups. For each group in that set we then

apply the same logic to the remaining letters. So for the group (A,B) we

have C,D,E,F left over. We again get every way to get choose 2 of the now

4 people and add that group to (A,B). Again we get something like:

(A,B) (C,D)

(A,B) (C,E)

(A,B) (C,F)

(A,B) (D,E)

(A,B) (D,F)

(A,B) (E,F)

Finally we do it one last time, this time though it is easy, because we are choosing 2 people out of a remaining 2 people for each grouping so far there is only one option. So the above groupings respectively turn into:

(A,B) (C,D) (E,F)

(A,B) (C,E) (D,F)

(A,B) (C,F) (D,E)

(A,B) (D,E) (C,F)

(A,B) (D,F) (C,E)

(A,B) (E,F) (C,D)

Once we do this for every group that we started with back in step one we have

our list, now with no more confusions between (A,B) and (B,A). We

still have a problem though and that is that we are still getting duplicates

in the form of

(A,B) (C,D) (E,F) vs (A,B) (E,F) (C,D). (Lines 1 and 6 above)

I didn’t notice this back when I first wrote it and so as far as I was concerned this solution was optimal and got left alone for a year.

That Lurking Problem

So that problem I mentioned earlier… The logic in the program when it was first written was to generate all of the groups and then go through and score them, keeping track of the best group as we go and then displaying it at the end. Some of you reading might have already noticed the problem, but for those who haven’t yet, lets take a look at the numbers behind the two solutions we’ve looked at so far.

Solution #1’s Size

The first solution was basically just generating permutations and then grouping them. There exists \(n!\) (spoken as “n factorial”) ways to permute a set of n elements, and we would have been looking at all of them. Factorials get big fast, for example \(10! = 3{,}628{,}800\).

Thankfully I never implemented solution #1, so how about solution #2?

Solution #2’s Size

Solution 2 is a bit more complex but still not too bad. We were just choosing g elements (the number of people in a group, also known as \(\frac{n}{k}\)) repeatedly until we had nothing left. So we start with \({n \choose g}\) (spoken as “n choose g”). Then for each of those we have another \({n-g \choose g}\) possibilities this goes on until we have no more elements, so we can define the number of groupings \(P(n,k)\) as:

\[P(n,k) = {n \choose g} * {n-g \choose g} * ... * {g \choose g}\]Expanding this out using the following formula for combinations

\[{a \choose b} = \frac{a!}{b!(a-b)!}\]we get:

\[\require{enclose} \begin{eqnarray} P(n,k) &=& \frac{n!}{g!(n-g)!} * \frac{n-g!}{g!(n-g-g)!} * \frac{n-2g!}{g! (n-2g-g)!} * ... * \frac{2g!}{2g!(2g-g)!} * \frac{g!}{g!(g-g)!} \nonumber \\ &=& \frac{n!}{g!(n-g)!} * \frac{(n-g)!}{g!(n-2g)!} * \frac{(n-2g)!}{g! (n-3g)!} * ... * \frac{2g!}{g!(g)!} * \frac{g!}{g!} \nonumber \\ &=& \frac{n!}{g!\enclose{horizontalstrike}{(n-g)!}} * \frac{ \enclose{horizontalstrike}{(n-g)!}}{g! \enclose{horizontalstrike}{(n-2g)!}} * \frac{ \enclose{horizontalstrike} {(n-2g)!}}{g! \enclose{horizontalstrike} {(n-3g)!}} * ... * \frac{\enclose{horizontalstrike} {2g!}}{g!\enclose{horizontalstrike} {(g)!}} * \frac{\enclose{horizontalstrike} {g!}}{g!} \nonumber \\ &=& \frac{n!}{(g!)^{\frac{n}{g}}} \nonumber \\ &=& \frac{n!}{(\frac{n}{k}!)^k} \end{eqnarray}\]It isn’t the prettiest result in the world, but it is immediately clear that we’re doing better than the base \(n!\) we got from solution 1. In fact, for 10 people in 2 groups, there are only 252 possible groupings according to this result, much better than 3.6 million!

Very Large Numbers

There is still a problem though, because we have duplicates with regards to the ordering of the groups that means that for k groups we will have \(k!\) duplicates of each grouping. This isn’t really a problem for a small gathering where we’re ordering two or 3 pizzas, but when everybody gets together to help a friend move and we’re ordering 5 or 6 pizzas it means that each grouping has 720 duplicates. Using the above formula, 18 people into 6 groups gets you \(P(18,6) = 137{,}225{,}088{,}000\).

One Hundred and Thirty Seven BILLION.

Combine that with the fact that the program was written in python and the scoring function wasn’t perfectly optimized means that there was no way a request for 18 people and 6 pizzas was ever going to give a solution that day. So when we were all done moving I heard to my surprise that the pizza app had failed and that they just ordered some pizzas that would probably be good. Stuck with mediocre pizza choices again, I vowed to fix the pizza app once and for all that weekend.

Fixing It

A number of fixes were implemented immediately to make scoring the groupings faster:

- Generate common sets such as which toppings a person is okay with once for each person at the start and not each time.

- Use Numpy to multiply and sum the arrays representing people’s scores

- Use memoization to ensure that the score for each group of people is only computed once.

With those in place, the program is able to score more than 100,000 groupings per second, but that still won’t allow us to compute all 137 Billion of P(18,6).

Solution #3

Which brings us to solution #3. The problem with solution #2 was that it had duplicates with regards to the ordering of the groups. To fix that we just have to specify and enforce an ordering of the groups, ensuring that there is exactly one valid way to represent each grouping. The new algorithm is as follows:

- Start by putting the person that comes first alphabetically in the first position in the first group.

- For every other spot in each group, try inserting each person one by one, skipping people who have already been inserted.

- If this is the first position in a group, only insert the person if they come after the first person in the previous group alphabetically

- If this is not the first position in a group, only insert the person if they come after the previous person in the group alphabetically

- Once a person is inserted, recurse to the next position.

- If all spots have been filled, that is a possible grouping

This will generate all possible groupings and only generate each possible grouping exactly once. There are a number of short circuit mechanisms and heuristics that can make things go faster than exactly following the above steps but those are just implementation details.

Solution #3’s Size

We’re going to cheat a bit on this step and rather than derive the formula for the number of possible groupings from the method we’re just going to say that because this method generates the same number of groups as the last method but without the \(k!\) duplicates for each group. So we get:

\[P(n,k) = \frac{n!}{(\frac{n}{k}!)^k} * \frac{1}{k!} = \frac{n!}{k!(\frac{n}{k}!)^k}\]Now \(P(18,6) = 190{,}590{,}400\), which could actually be computed in some reasonable time (30 minutes) if you really wanted to check all of them. But that time doesn’t cut it for loading a web page.

Surrendering to the numbers

The nasty part about this problem being exponentially hard is that even if I could speed things up to make \(P(18,6)\) reasonable for a webpage, P(24,6) would still be just as unreasonable. I had to come up with a solution that would work no matter how many people or pizzas were requested. So I gave up on finding the *perfect* pizza in those cases and instead just find the best pizza from the first 1 million generated groupings. Thanks to the new recursive algorithm, any time I get to the base case and find a valid possible grouping I check it, and record it if it beats the current best. Now the webpage will almost always load in under 30 seconds even for the most taxing queries.

The Odd Cases

You might have noticed that up until now I’ve been conveniently avoiding talking about numbers of groups that don’t evenly divide the number of people. All of the generating methods up until now will work when given a set of not equally split groups. What won’t work is the size calculations. The size calculations for solutions 2 and 3 rely on the fact that \(\frac{n}{k}\) is an integer.

I had an efficient working way to generate the groupings, I could just stop now, the pizza app would work just fine. But I couldn’t do that, I was already too curious.

Solution #3’s *Actual* Size

So the first thing to mention is that there is basically no material that I can find on the subject of evenly dividing n items into k groups. Hundreds of forum and stackexchange posts on dividing n items unevenly into k groups, basically nothing I could find about dividing into groups evenly. The closest I got was this sequence in the On-line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences, which describes the result we just got above for when k evenly divides n. If I wanted to know this, I was going to have to do it myself.

I’ll spare you the failed conjectures I thought of in the 5 or so hours I spent staring at and working through examples figuring out the correct answer and just jump straight into the logic behind my final answer.

When n is not evenly divisible by k, when dividing the people into the groups as evenly as possible we’ll end up with some number of “smaller” groups and some number of “larger” groups where the larger groups each have one more person than the smaller groups. For example, dividing 10 people into 4 groups would result in two larger groups and two smaller groups with the larger groups having three people and the smaller groups having two people.

The key realization here is that because the possible re-orderings of groups are separate between the set of larger groups and the set of smaller groups it is possible to split the problem into two sub problems. Lets define some terms:

\[\begin{aligned} A &= n \bmod k & \text{(number of large groups)}\\ B &= k - (n \bmod k) = k - A & \text{(number of small groups)}\\ g_a &= \Bigl\lceil\frac{n}{k}\Bigr\rceil & \text{(group size for large groups)}\\ g_b &= \Bigl\lfloor\frac{n}{k}\Bigr\rfloor & \text{(group size for small groups)}\\ n &= A * g_a + B * g_b\\ \end{aligned}\]So when the groups don’t divide evenly, first choose \(B * g_b\) of the n people. Then for each of set of \(B * g_b\) people you find all of the groupings of that separate people into \(B\) equally sized groups of \(g_b\) people each. Then for the remaining \(A * g_a\) people, you find all of the groupings that separate people into \(A\) equally sized groups of \(g_a\) people each. Combine each grouping from the first step with each grouping from the second step, repeat for each choice of \(B * g_b\) people and you have all possible groups with no duplicates.

To state it more mathematically:

\[P(n,k) = \left\{ \begin{aligned} &n \bmod k = 0 :& \frac{n!}{k!(\frac{n}{k}!)^k}\\ & n \bmod k \neq 0 :& {n \choose B*g_b} * P(B*g_b,B) * P(A * g_a,A) \end{aligned} \right.\]And because we can guarantee that for both instances of P(n,k) in the bottom part of the function defined above that k divides n evenly, we can just substitute in the top part of the above formula and get a unifying formula for all n and k.

\[\require{enclose} \begin{eqnarray} P(n,k) &=& {n \choose B * g_b} * P(B * g_b,B) * P(A * g_a,A) \\[10pt] &=& {n \choose B * g_b} * \frac{(B * g_b)!}{B! * (\frac{B * g_b}{B}!)^B} * \frac{(A * g_a)!}{A! * (\frac{A * g_a}{A}!)^A}\\[10pt] &=& \frac{n!}{(B * g_b)! (n - (B * g_b))!} * \frac{(B * g_b)!}{B! * (\frac{B * g_b}{B}!)^B} * \frac{(A * g_a)!}{A! * (\frac{A * g_a}{A}!)^A}\\[10pt] &=& \frac{n!}{(B * g_b)! (n - (B * g_b))!} * \frac{(B * g_b)!}{B! * g_b!^B} * \frac{(A * g_a)!}{A! * g_a!^A}\\[10pt] &=& \frac{n!}{(B * g_b)! (A * g_a)!} * \frac{(B * g_b)!}{B! * g_b!^B} * \frac{(A * g_a)!}{A! * g_a!^A}\\[10pt] &=& \frac{n!}{B! * g_b!^B * A! * g_a!^A}\\[10pt] &=& \frac{n!}{A! * B! * g_a!^A * g_b!^B}\\[10pt] &=& \frac{n!}{(n \bmod k)! * (k - n \bmod k)! * \bigl\lceil\frac{n}{k}\bigr\rceil!^{(n \bmod k)} * \bigl\lfloor\frac{n}{k}\bigr\rfloor!^{(k - n \bmod k)}}\\[10pt] \end{eqnarray}\]Again, not the prettiest of formulas but I’m not sure that there is any further way to simplify this. Personally, when writing it out I prefer defining \(A\) and \(B\) off to the side and then just writing the second to last line from above.

Results and Future Work

I have submitted the new sequence to the OEIS, and pending the approval process it will be A308624. Hopefully this work finds its way to someone else looking for this problem at some point in the future.

The only real place to go from here would be to account for how much pizza each person wants to eat when deciding the groups, but I’m pretty sure that just becomes equivalent to the bin packing problem but worse, which I don’t care to deal with just yet.

-Dillon